I’d like to tell you the story of a melody that started its life in the the 17th century as young man’s lovesick lament and was then, in succession, transformed into a hymn sung by Germany’s Lutheran faithful, appropriated by a composer–considered by some the greatest that ever lived–for one of his crowning achievements, and then, over two hundred years later, was spun into a rumination on the American experience at a time when the Watergate scandal was roiling to a full boil and the U.S. was beginning its withdrawal from Vietnam. Intrigued? I hope you’ll read on.

I. A Secular Start

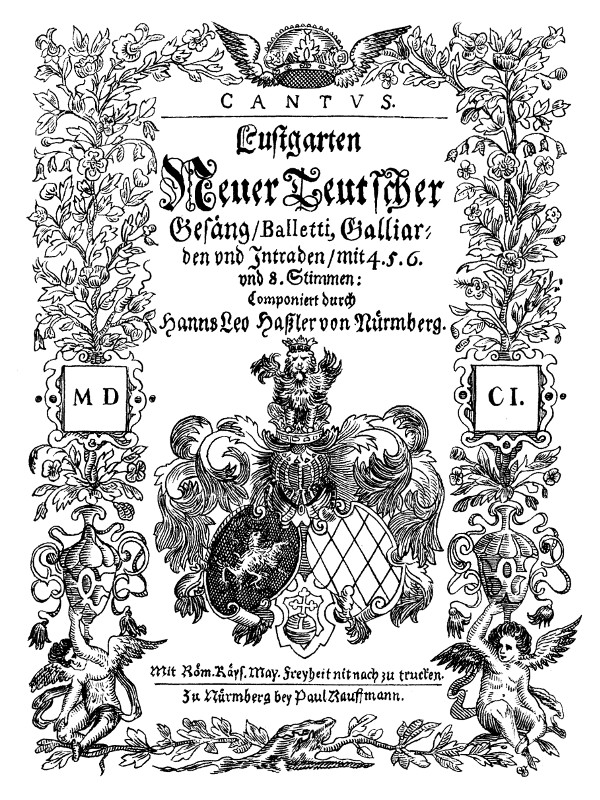

In 1601, Hans Leo Hassler (1564 – 1612), a German composer and organist, published a volume of music called Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesäng, Balletti, Gaillarden und Intraden (A Pleasure Garden of New Teutonic Songs, Ballets, Gaillards and Intradas). Of the 50 compositions included in the collection, 39 were vocal works and 11 were instrumental selections.

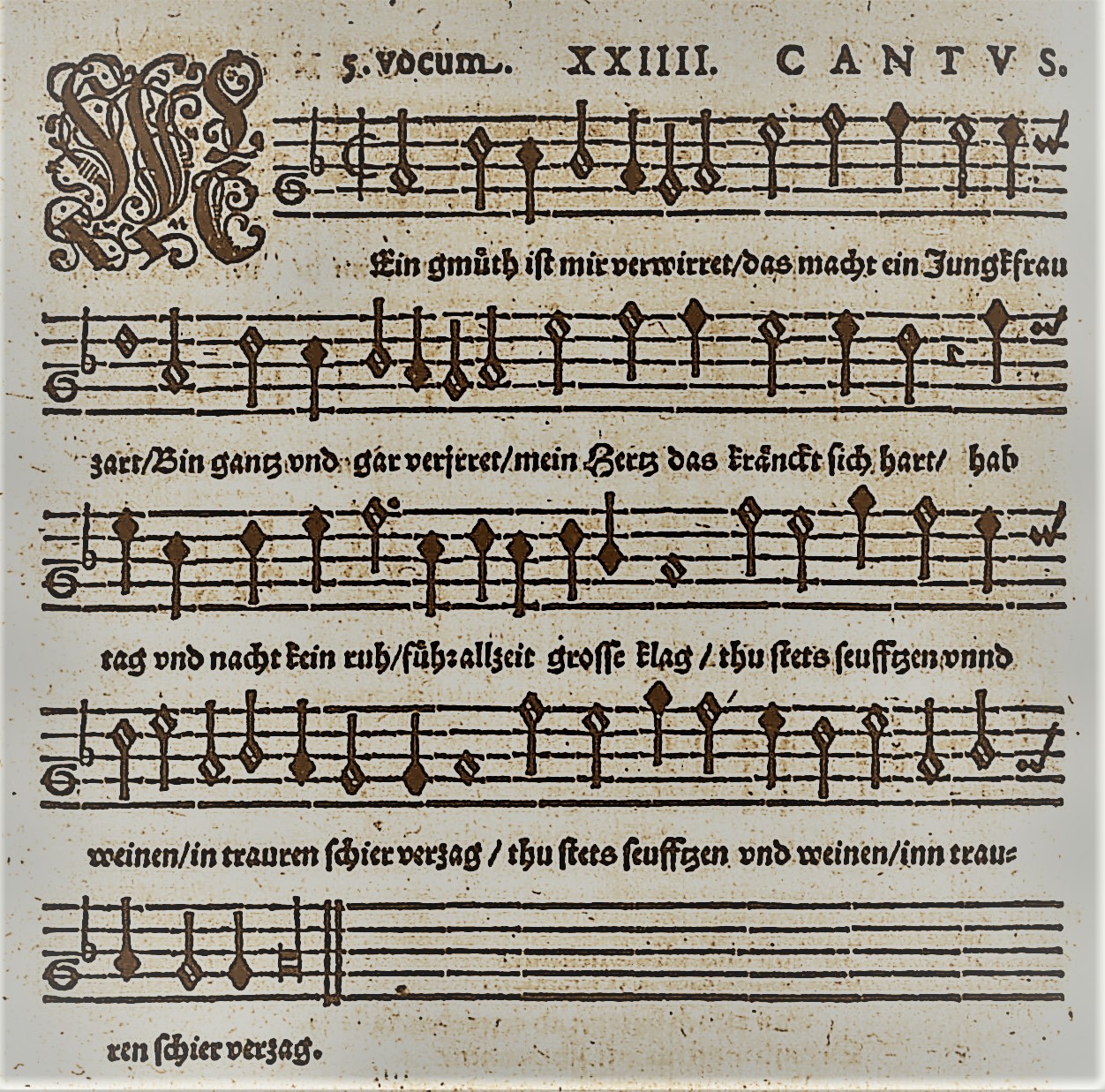

One of the vocal works was a secular love song, to be sung by five voices, called “Mein G’müth ist mir verwirret” (“I’m all mixed up”).

Here’s the first of the five verses performed by the German vocalists, Ensemble Diapasón.

Mein Gmüth ist mir verwirret,

das macht ein Jungfrau zart,

bin ganz und gar verirret,

mein Herz das kränckt sich hart,

hab tag und nacht kein Ruh,

führ allzeit grosse klag,

thu stets seufftzen und weinen,

in trauren schier verzag

I’m all mixed up;

This, a tender maid has done to me!

I’m totally lost;

My heart is sick and sore.

I get no rest by day or night,

My pain is always so great.

I’m sighing and crying all the time;

I’m almost in despair.

II. A Hymnist’s Prerogative

Let’s remain in Germany and move further into the 17th century. Meet Paul Gerhardt (1607 – 1676), a theologian, Lutheran minister and prolific creator of hymns.

As a theologian and minister, Gerhardt would have been familiar with a medieval poem, Salve mundi salutare (All Hail, Savior of the World). The poem consisted of seven cantos, each of which addressed a part of Jesus’ body–his feet, knees, hands, side, breast, heart, and head–as he was dying on the cross. Gerhardt translated the entire work into German from its original Latin and in 1656, the seventh section, Salve caput crucentatum, which focused on Jesus’ head, was set to a rhythmically simplified version of Hassler’s love song melody and published in a popular hymnal of the day. The well-known first line of the hymn: “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” (“O Sacred Head Now Wounded”).

III. The Master

J.S. Bach was born 9 years after Gerhardt died. An extraordinarily devout Lutheran, he would come to know Gerhardt’s hymns well and, in 1727, would weave the melody of “O Sacred Head” into one of his own works. Hassler’s lovesick lament was now placed in the service of “passion” of a very different kind: the Passion story (from passio, a participle of the Latin verb “to suffer”), which recounts the events leading to Jesus’ crucifixion. Bach’s sacred oratorio, the St. Matthew Passion, has been referred to by many as the Mount Everest of Western music. This monumental work, written for three choirs, two orchestras and multiple soloists, is three hours long and was first performed in Leipzig on Good Friday in 1727.

The Saint Matthew Passion, in addition to arias and recitative, contains twelve chorales, hymn tunes arranged in four-part harmony, i.e., for soprano, alto, tenor and bass voices. (Contrast this with what generally happens during a church service, with members of the congregation all singing the same melodic line accompanied by an organ). Hassler’s melody, the so-called “passion chorale”, is heard five separate times over the course of the oratorio. Repetitive? Boring? Not a chance. Bach’s harmonizations allow each appearance of the chorale to effectively convey the mood of what’s happening at that time in the Passion story.

I’ll offer two examples, using video snippets of a performance by Philippe Herreweghe and the Collegium Vocale Gent. The first time we hear the melody, it’s paired with text representing a worshiper asking for Christ’s acceptance and acknowledging the spiritual blessings he provides. The sentiments are uplifting, befitting the bright key of E major.

Erkenne mich, mein Hüter,

Mein Hirte, nimm mich an;

Von dir, Quell aller Güter,

Ist mir viel Gut’s getan.

Dein Mund hat mich gelabert

Mit Milch und süßer Kost;

Dein Geist hat mich begabet

Mit mancher Himmelslust.

My Shepherd, now receive me

My Guardian, own me Thine.

Great blessing Thou didst give me,

O source of gifts divine.

Thy lips have often fed me

With words of truth and love;

Thy Spirit oft hath favored me

To heavenly joys above.

The fifth and final time we hear the chorale is in the moments after Christ’s death. The melody is the same, but the harmonization–with its many accidentals and discordant intervals–conveys a vastly different, and appropriate, mood: one of anguish. The words are, again, those of a worshiper, this time pleading for Christ’s presence at the time of his/her own death. This particular setting of the chorale is, for me, almost unbearably beautiful; its mere minute and sixteen seconds contain an entire world of emotion.

Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden,

So scheide nichts von mir.

Wenn ich den Tod soll leiden,

So tritt du dann hierfür.

Wenn mir am allerbängsten

Wird um das Herze sein,

So reiß mich aus den Ängsten

Kraft deiner Angst und Pein.

My Savior, be Thou near me

When death is at my door.

Then let Thy presence cheer me,

Forsake me nevermore.

When soul and body languish,

Oh, leave me not alone,

But take away mine anguish

By virtue of Thine own.

[Now two brief personal comments. The first is that I went to a performance of the St. Matthew Passion last Sunday, and each of the five iterations of this melody raised gooseflesh, thus inspiring this post. The second is that I was baptized and confirmed in the faith so deeply felt by Gerhardt and Bach and I’m grateful I was, because it exposed me to some important sacred music traditions. As an adult, however, organized religion has not been a key part of my life. Among the bits of paper ornamenting my refrigerator door is this quote: “I don’t go to church. It’s how you behave in life, not whether you go to church and pray, that makes you a worthy human being.” Music and art are my religion.]

IV. Circling Back To The Secular

Drawing to a close now in what is easily the longest post I’ve done here at Augenblick.

Paul Simon’s second solo album, There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, was released in 1973 and included the song “American Tune”; Simon isn’t addressing passion, or ‘The Passion’, but rather the sense of weariness, uncertainty, and misdirection that pervaded the country at the time. The melody is clearly inspired by the work of Hassler, who, I imagine, might be nonplussed to learn that his composition, 417 years after he committed it to parchment for the first time, is thriving well into the 21st century.

Many’s the time I’ve been mistaken

And many times confused

Yes, and I’ve often felt forsaken

And certainly misused

Oh, but I’m alright, I’m alright

I’m just weary to my bones

Still, you don’t expect to be bright and bon vivant

So far away from home, so far away from home

And I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered

I don’t have a friend who feels at ease

I don’t know a dream that’s not been shattered

Or driven to its knees

But it’s alright, it’s alright

For we lived so well so long

Still, when I think of the

Road we’re traveling on

I wonder what’s gone wrong

I can’t help it, I wonder what has gone wrong

And I dreamed I was dying

I dreamed that my soul rose unexpectedly

And looking back down at me

Smiled reassuringly

And I dreamed I was flying

And high up above my eyes could clearly see

The Statue of Liberty

Sailing away to sea

And I dreamed I was flying

We come on the ship they call The Mayflower

We come on the ship that sailed the moon

We come in the age’s most uncertain hours

And sing an American tune

Oh, and it’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright

You can’t be forever blessed

Still, tomorrow’s going to be another working day

And I’m trying to get some rest

That’s all I’m trying to get some rest.

Very cool backstory Jeanno! I’ve always loved this song and lyric— and I always enjoyed, as a kid, discovering that a tune had been lifted from a much older piece. My favorite was Lover’s Concerto which I first heard on the radio, and then later on, played on the piano in one of my classical songbooks. Imagine my surprise when I realized that I already knew the melody!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I almost mentioned that offering from The Toys! (“How gentle is the rain….”) 🙂

Thanks so much for reading and commenting, Lori!

LikeLike

What a journey! It will not surprise you in the least that I am only familiar with the final ‘version’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I bet you’re not alone (and that’s NOT a criticism of the people in that category). That’s one of the many wonderful things about music: the way it can inspire, and be reimagined by, those who come after. Thanks for giving this one a whirl, Bruce. Even as I was writing it, I suspected that the length, multiple videos and more serious subject matter would be a bit off-putting to many.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I recently heard that the maximum post length one can, in 2018, expect blog readers to read in its entirety is approximately 500 words.

Certainly I’ve noticed that longer posts are getting less attention these days. What, if anything, to do?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have some thoughts that I’ll share under separate cover!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A weird ESP as I heard this song on a Paul Simon disc driving home from a Passover seder late last night. I had no idea about the rich past. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😉

LikeLike

Jeanne,

Being a great fan of Bach, I am going to wait until this weekend so that I can devote a solid hour to reading the lyrics and your analysis, and listening to the music. I cannot wait! – Vince

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vince, this post has garnered few eyes (and even fewer comments, as you can see), so if you’re so moved I’d love it if you would circle back to let me know what you think. (This post was a real labor of love, in both senses of the word: I *love* what Bach does with the melody, AND I had to re-write/re-construct over half of the post (*labor*) after my browser crashed and gobbled up hours of work.)

LikeLike

Jeanne, I did indeed read and listen to this post this weekend, and what a treat! The persistence, or reuse, of the melodies and themes for over 350 years, all the way to Paul Simon is great. Makes me wonder if the music started out as some Germanic tribal chant that Herr Hassler adapted. Listening to Paul Simon and reading his lyrics – what a great connection: music as time-travel.

I’m a fan of JSB, but not very familiar with the St. Matthew’s Passion. I think it’s time to correct that. I am a fan of Phillip Herreweghe’s Bach recordings, especially his Mass in B Minor, so I’ll start with that.

Thanks, as always, for sharing! – Vince

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vince, thank YOU for taking the time to absorb the full message of the post. The St. Matthew Passion really is glorious (I like it much more than the St. John Passion). In addition to the chorales I mention in the post, there are some lovely arias, of which “Erbarme mich” is probably the best known. You can’t go wrong with Herreweghe’s interpretations of Bach; John Eliot Gardner is also excellent. Again, my thanks to you for visiting!

LikeLike

… I mean I’ll start with Herreweghe’s recording of St. Matthew’s Passion …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, I found this post when looking for a decent translation of the Hassler tune. Thanks for this and the whole post! I conduct an elders’ choir in Boston that meets at our local library and we’re doing a set of: me singing the Hassler tune, without words, just to give the audience a taste of the original melody, followed by the Peter Paul and Mary version (“Because all men are brothers”, text modified by one of our choristers)(in which I also simplified Bach’s harmonies to make the tenors and basses sing one part–we have a lot of non-readers), then our pianist is going to improvise a bit wildly, ending up on the Xmas Oratorio version of the chorale, which is my favorite. So, we are in the same universe of appreciation of this magical tune. Alas, we could not pull off Paul Simon’s version with a choir, but I’ll tell the audience about it. So, thank you again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Elizabeth, I’m delighted you landed on my post and even more delighted that you found it informative. Your undertaking with the elders’ chorus sounds wonderful: good luck with the performance!

LikeLike

I stumbled upon this post as I was looking for more info about Leo Hassler and Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden. I recently discovered a ‘choral’ setting for strings of Hassler’s tune by George Templeton Strong, written in the dark days of October 1929. I plan to perform it with Juno Orchestra in Vermont in February. I’m a big fan of Bach, and love his various settings of O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden (among so many other things, right?). I appreciate your thread and connections here. I did not know the Paul Simon. Listening, I got goosebumps thinking about the passage of time, the universality of all music. And now, thanks to Elizabeth (just above, whom I met a few times in the 1980s), I want to find Peter, Paul, and Mary addressing the same tune. Thank you. It’s heartening to find others in the same part of the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very belated thank you for your comment; I hope your performance with Juno Orchestra goes well this month!

LikeLike